As usual it is wonderful to return to Saint Louis and take up the chores of GM-In-Residence for the Club. Of course my main purpose on this trip was to come for the 2017 U.S. Championships as a commentator along with Jennifer Shahade and Maurice Ashley. I really do enjoy the classes, lectures, instruction, as well as the private lessons. It is all good. One additional request was asked of me and one that I was more than happy to accept: Could I please say a ‘few words’ for the introduction of Victor Kortchnoi for the World Chess Hall of Fame? Could I ever! You bet! As a close personal friend of Victor, I have enormous respect for this towering legend. So, I worked on what I hoped would be a heart-felt tribute. Then, days before the Opening Ceremonies, I was told that our speeches had to be short. As in real short. As in one minute in length. Gasp. How can you pay tribute to a chess-god in one minute? The best I could do is to make an extreme abbreviation of the speech I intended. Please find my intended words below:

Comments for Victor Lvovich Kortchnoi Induction into the World Chess Hall of Fame

Ladies & Gentlemen,

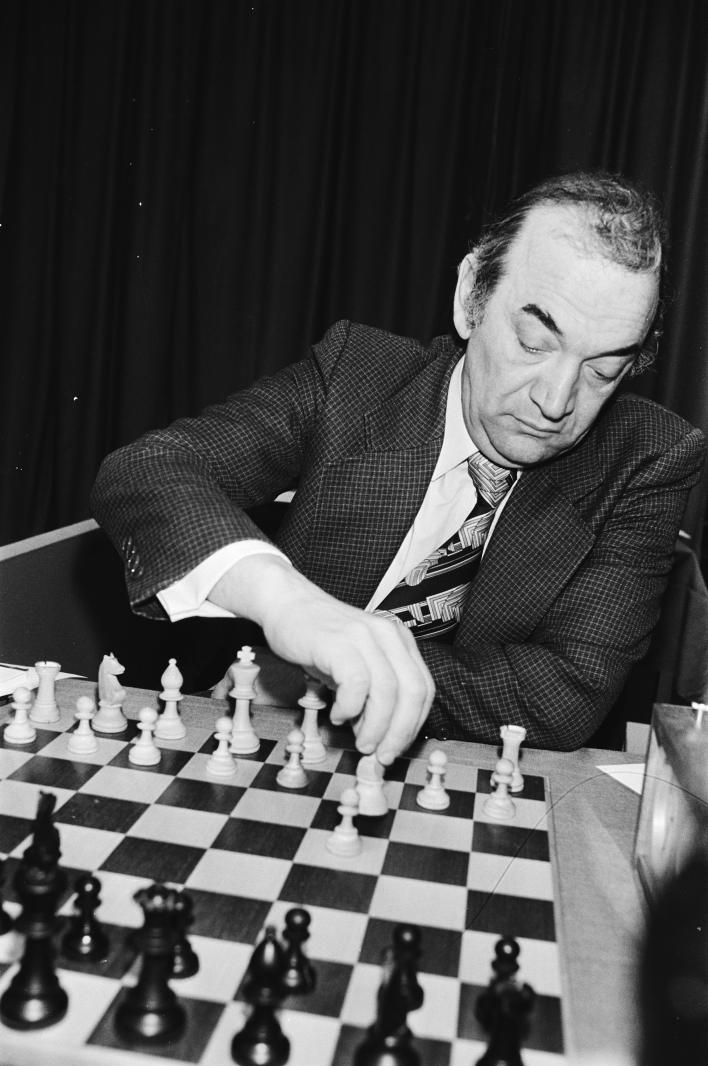

Victor Lvovich Kortchnoi was a colossus straddling the chess world for decades as an elite Grandmaster. At times, an abrasive personality he could also be congenial, generous, even tender. A gentleman with old world manners. A fierce competitor, a fighter, a warrior, Victor’s fiery outbursts were legendary. Grandmasters often joked, “If Victor didn’t criticize you personally – you simply weren’t a player of any worth.” Victor was also a close personal friend to whom I owe an enormous debt of gratitude.

To better understand Victor, the person, you have to start with his upbringing. Victor was born on March 23, 1931 in Leningrad, the USSR, which is now known as St. Petersburg, to a Jewish mother, Zelda Gershevna Azbel and a Polish-Catholic father, Lev Merkuryevich Kortchnoi. You can readily imagine the conflicts in that family!

His mother, Zelda, was a daughter of the Yiddish writer Hersh Azbel. She was a pianist and alumna of the Leningrad Conservatory of Music. His father, Lev, was an engineer. Both parents came to Leningrad with their families from the Ukraine in 1928. After their divorce, Victor lived with his mother until 1935, then with his father, paternal grandmother and later his adoptive mother. Children are always victims in divorces and Victor’s unsettled upbringing robbed him of his childhood and caused him to be determinedly self-reliant.

It is impossible for most American’s to empathize with Victor’s childhood. With the exception of Pearl Harbor, all the fighting in WWII happened overseas, as in “over there.” The USSR was invaded by the bulk of German forces with horrifying results. The siege of Leningrad is considered to be the worst fighting of any of the battles that occurred in what the Soviet’s dubbed the “Great War.” Victor’s father, Lev, was killed in the siege of Leningrad in 1941. Victor was ten years old. He would be raised by his adoptive mother Roza Abramovna Fridman in extremely difficult conditions. Victor survived and after the war graduated from the Leningrad State University with a major in history.

In the USSR, Victor felt constrained. Alternatively, either because of his Jewish ancestry or because he was dubbed as he put it, “a so called intellectual.” In either case, he chafed under the USSR’s Sport’s authority. But my remarks today are not about a young boy from Leningrad who lost his parents in WWII but about a remarkable player who would challenge the USSR as a prominent defector and become one of the most successful and long-lived legendary players.

Victor learned to play chess about the age of five and so began his assault on Mount Olympus.

Consider that Victor was a Candidate for the World Championship ten times: 1962, 1968, 1971, 1974, 1977, 1980, 1983, 1985, 1988 and 1991. That is an extraordinary span of time.

In the ‘60s, it was considered as hard to become USSR Champion as it was to become World Champion. Victor won the USSR Chess Championship four times. He was a five-time member of Soviet teams that won the European championship, as well as a six-time member of Soviet teams that won the Chess Olympiad. He is the only player to have won or drawn (in individual game(s)) against every World Chess Champion, disputed or undisputed, since World War II. He played in both USSR versus The Rest of the World matches, once, for the USSR and once for the Rest of the World Team. A warrior the whole of his life, in September 2006, Victor won the World Senior Chess Championship.

This thumbnail sketch of his career doesn’t come close to listing all the titles and achievements he won. It would be a very, very long presentation if it did. Instead, I’d like to briefly focus on Victor’s three bids to become World Champion.

Anatoly Karpov and Victor Kortchnoi qualified to the 1974 Candidate’s Finals match. The winner would become the official Challenger and play Bobby Fischer in 1975. As Bobby would decline to play in the 1975 World Championship match, the Candidate’s Final became a de-facto World Championship match.

Prior to this, all important Candidate’s Finals matches were played in an intense atmosphere. Former World Champion Tigran Petrosian made a public statement against Kortchnoi that was supported by the Soviet Chess Federation. Essentially, Tigran stated that the generation of himself and Kortchnoi could not successfully compete against Fischer. Instead, it was necessary to develop younger players, such as the youthful Karpov. The message was clear, “Out with the old generation and in with the new generation.” Karpov was anointed as the chosen favorite of the Sports Commissars. Victor was not. During the Candidate’s Finals Match it was impossible for Victor to get assistance from his fellow grandmasters. Only David Bronstein and Roman Dzindzichashvili, working in secret, helped him and only through furtive phone calls. On the other hand, Karpov enjoyed all the benefits that the Soviet State could offer including a team of grandmasters to help his training. Victor narrowly lost the Final’s 24-game Match 12.5-11.5. A single game separated the two players.

It was at the closing ceremony of the Candidates' Final when Kortchnoi made up his mind up that he would have to leave the Soviet Union. The problem was that the USSR Sports Committee prevented Kortchnoi from playing any international tournaments outside the USSR. Even when Kortchnoi was invited by GM Paul Keres and IM Iivo Nei to participate in a 1975 International Tournament in the Estonian Republic of the USSR, an internal event, Kortchnoi was not allowed to play. For their efforts, both Keres and Nei were reprimanded. Keres did play a short, secret training match at Tallinn 1975, with Kortchnoi, who won (+1=1).

Kortchnoi was then allowed to play the Soviet Team Championship and an international tournament in Moscow later in 1975. The ban against Kortchnoi competing outside the USSR was lifted when he accompanied fellow veteran GM’s, Mark Taimanov and David Bronstein, to London to play a Scheveningen-style event (where each team member competes against only the other team's players) against three talented young British masters Jonathan Mestel, Michael Stean and David Goodman. Kortchnoi then played the international tournament at Hastings, 1975-76.

Skipping well ahead in my story, Victor, in a 2006 lecture in London, mentioned that the breakthrough that allowed him to resume international appearances came when Anatoly Karpov became World Champion (by forfeit over Bobby Fischer). Questions arose about how Karpov had qualified to be a World Champion – every game that he played in the whole qualification cycle was played on Soviet soil. How strong, after-all, was Karpov? He had never played Fischer. Since Kortchnoi was not publicly visible, it was largely believed that Karpov was not deserving to be called World Champion. Kortchnoi was then allowed to play the 1976 Amsterdam tournament, as a means to prove Karpov was a worthy World Champion. The Soviet thinking went that if Victor won, it would prove he was a strong Grandmaster, who had been defeated by Karpov.

Let us return to 1976. As it turned out, Kortchnoi was joint winner of the tournament, along with GM Tony Miles. At the end of the tournament, Victor famously asked Tony, “How do you spell ‘political asylum’?” Tony grabbed a piece of paper, wrote it down for him and Kortchnoi entered a police station declaring his desire to defect.

Victor Lvovich Kortchnoi became the first strong Soviet chess grandmaster to defect from the Soviet Union. While many would follow, Victor had to leave his wife, Bella, and his son, Igor, behind. The defection resulted in a turbulent period which was – at all times – overshadowed by the oppressive political climate of the Cold War. For many defectors, as well as would be defectors, Victor was a trailblazing hero. In his home country, he was branded both a criminal and a traitor. As a defector, Victor would live in fear of extradition, kidnapping as well as assassination.

Kortchnoi defected in the Netherlands in 1976, but would move to Switzerland in 1978 and naturalize as a Swiss citizen. Playing in the 1975-78 World Championship cycle, Victor emerged as Challenger. He would play against Karpov a match in Baguio City in the Philippines. The Soviet’s fought tooth and nail to exclude Kortchnoi from the cycle. Protesting at every possible event, arguing that his qualification in the cycle came from his being a representative of the Soviet State, that his qualification spot belonged to the Soviet Chess Federation. During the match, protests took on a surreal theater: Hypnotism, X-Rays, Yogurt, Mirrored sunglasses, Parapsychologist, Treachery, as well as Yogi’s were all thrown into the mix of reports on the match. The rules were that the winner would be the first to win six games. Draws excluded. At the demand of the Soviet’s, Victor would play under the FIDE flag, not the Swiss flag. After months of battle and 31 games, the match was tied 5-5. Karpov won game 32 and retained his title. Once again, Karpov would win the title by a single game. Kortchnoi would go to court declaring that the Soviet’s had violated an agreement. The judge would rule in his favor, that the Soviet’s had indeed violated the match agreement, but would not overturn the sporting decision.

Once more, Kortchnoi would have to go through a brutal Candidate’s cycle process from 1980-1981. And once more, he emerged victorious as the Challenger. I would join him on this leg of his remarkable life journey. Over a 20-month period, I spent 11 months with Victor. I was but twenty years old. I learned a lot.

While there are many stories I like to tell about my experience with Victor, two in particular stand out and I relish retelling them. The first is how I became Victor’s “second” or “trainer.”

In January 1980, I received an invitation to play in my first “big-league” elite event, Wijk Aan Zee. As a rookie, I was the designated target. It didn’t work out as scripted. I tied for first in the event, alongside six-time U.S. Champion Walter Browne. In round two, I faced and won my game against Victor. Our post-mortem analysis lasted for hours. The thrill – for me at least – was indescribable. Over the course of the tournament, Victor would often come up to me during play and ask me what I thought of so-and-so’s position. I’d tell him. He would pull a face of agreement and walk away. After the event, Victor came to me with a life-changing proposition, “Yasser, how would you like to be my second?” Victor asked. I was stunned into silence – perhaps for the first time in my life. So many thoughts raced through my head. “What could I possibly teach Victor Kortchnoi?” I thought. As my thoughts collided for attention one thought stood above all the rest, “Could I afford it?” and “How much would I have to pay to train with Victor?”

Fortunately for me, Victor completely misunderstood my silence. Instead he ventured, “Sorry. For conditions, I pay all your expenses including meals. I also pay you 500 Swiss Francs per week.” Still incapable of speech, I understood that Victor was offering to pay me to train with him. I stuck out my hand and we shook. I was over-the-moon with elation.

That was January 1980. Two months later, I would travel to Zurich to begin training with Victor. He picked me up and over dinner as well into the night we talked about our training sessions. Abruptly at about 11 PM Victor stopped and exclaimed, “You must be exhausted!” I was. I had been traveling for about 23 hours. Connections were awkward in those days. We were both saying our final goodnights and heading into the guest bedroom. We got into argument, “You take the master bedroom,” Victor insisted. I was elated to be in Victor’s company. Taking the master bedroom from him? Absolutely not. I dug in my heels. Eventually, Victor relented, explaining that he had a bad back, the mattress in the master bedroom was too firm and Victor preferred the bed in the guest room. “So I’d be doing you a favor by sleeping in the master bedroom,” I asked for confirmation. Victor was clear, he preferred the guest-bedroom. Well alrighty then, this was my lucky day!

We were saying our final goodnights and Victor confused me with a, “By the way, I hope you’re not nervous,” comment and closed the door. What was that? Victor’s English was passable but far from perfect. What did he mean? Instead of knocking and asking what he meant, I determined that I would use my Sherlock-Holmes like intellect to solve the riddle myself. Over the course of the next two weeks, Victor and I trained intensely. I mean 12 hours a day. If I thought I knew hard work, I was getting a whole new definition! During those two weeks, I came to know Victor very well. Victor saw his defection as a major blow to the Soviet Chess federation – a thought that made him very happy. He also saw himself as a great threat to the heavily coveted title of “World Chess Champion.” A title that the Soviet’s used for political, social and sporting purposes. In his view, the Soviet’s would stop at nothing to prevent him from dethroning Karpov, including assassination. What Victor was trying to say was that if the Soviet’s decided to send an assassin that night, he wouldn’t hit the guy in the guest room but the one in the master bedroom!

I became nervous, but only because Victor was so sure of his own fate!

I worked with Victor through the Candidate’s matches. He would again emerge as Challenger. Unfortunately, for him, in the World Championship Match in Merano, Italy, Victor was in atrocious form and lost the match 6-2 with ten draws. It was to be his last crack at the title.

Victor’s fiery temperament earned him the monikers, “Victor the Terrible” and more simply, “The Beast.” Victor did intimidate his over-the-board opponents! But before we remember him for these nicknames, let us remember him for an amazing sporting gesture. After Merano 1981, Victor was right back in the next Candidate’s Cycle. This time, a new star was rising from the East: Garry Kimovich Kasparov. In 1983, they were paired in the Semi-Finals together. Pasadena, California would host the match. The Soviet’s refused to send their new star and Victor won the match by forfeit. The Soviet’s would plead FIDE for a replay. Victor was under no obligation whatsoever to replay the match. He had won and could proceed to the Candidate’s Finals. Victor agreed to replay the match in London. He won the first game but lost the match. A new star, the Kasparov star, was reborn, but thanks only to Victor’s gracious gesture.

Today, I stand with you all to honor the memory of Victor Lvovich Kortchnoi. A great chess warrior. Victor would be elated, honored by his induction today into the World Chess Hall of Fame and he would thank you all. Each and every one of you for being here today. Rest in Peace, Victor.